Armachiana

The heading ‘Armachiana’, found in several display cases at the Museum, is a general term used to indicate that the information and objects relate to the development of Armagh city and county.

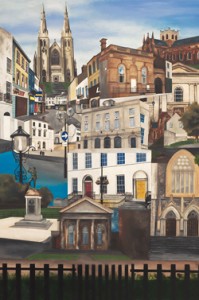

Although the site has been occupied since Neolithic times, the city’s foundation is traditionally associated with St Patrick, in 457 AD. Originally granted land by a local chieftain Daire, in the lower area of Scotch Street, Patrick finally secured the hilltop site where the Church of Ireland Cathedral now stands. This was the site of the great monastery of Armagh, where the Book of Armagh was compiled (807 AD).

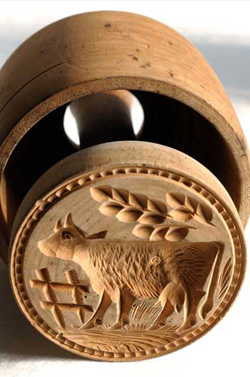

The impact of Christianity was felt throughout the county from objects like the Kilnasaggart pillar (714 AD), near Jonesborough, to the foundation of the Franciscan Friary (1263 AD) on the outskirts of the city. The trials and tribulations of religion and politics are reflected in objects like penal crosses and the toppling of the Market Cross (1813).

The contrast between Armagh in the centuries following St Patrick’s arrival and the image of the City in 1609 when it lay in ruins, could not be greater.

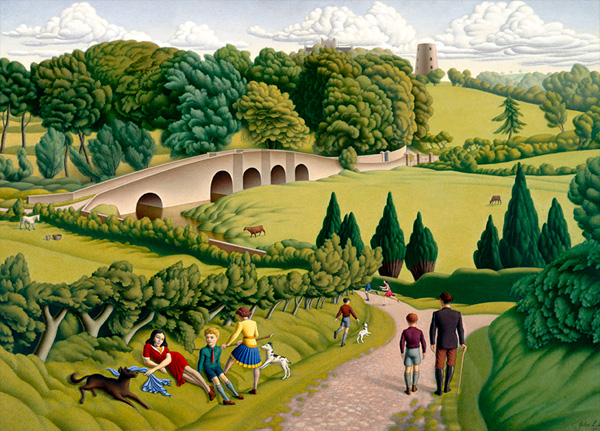

It was not until the arrival of Archbishop Robinson (1765) that the fortunes of the city were revived and many landmark buildings constructed, including the Observatory. Gradually the infrastructure that we associate with towns and cities was put in place, from the funding of a fire brigade to the provision of law and order.